This is a learning activity to encourage peaceful critical thinking about the situation that has been unfolding around COVID-19 vaccination policies.

Read the two passages below. Then reflect on the following questions:

(1) Under COVID, what does it mean to make decisions based on principle? What does it mean to make decisions pragmatically? Can you think of examples of decisions that you have made pragmatically and decisions that you have made out of principle?

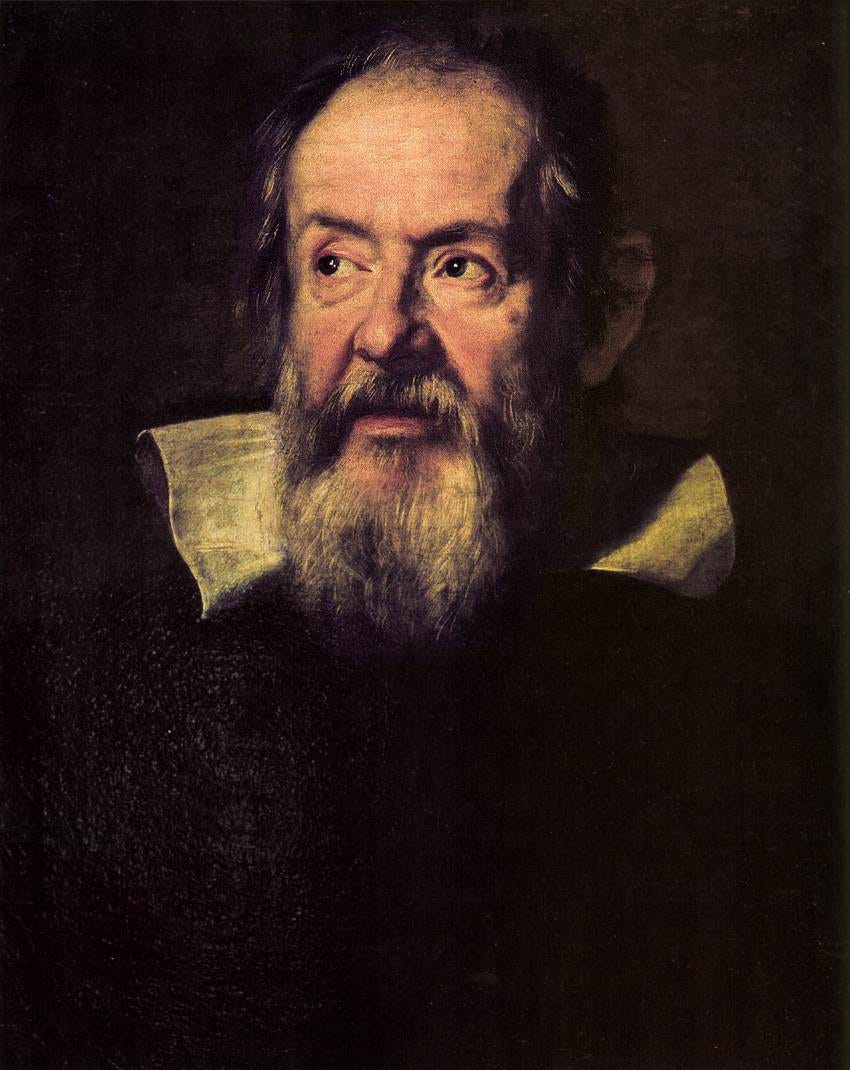

(2) Compare and contrast Galileo (as depicted in Brecht’s play) and Julie Ponesse.

(3) How has COVID changed or developed your view of ethics? Of science?

I have included my own cursory observations below the excerpts.

A transcript of Julie Ponesse’s video <

“My name is Julie Ponesse, and this message is about mandatory vaccination.

I am a Professor of Ethics at Huron College at the University of Western Ontario. It’s one of the largest universities in Canada. Today I am going to teach you a short lesson on the universally accepted ethics of coercing people into medical procedures. I’ll be the example.

My employer has just mandated that I must get a vaccine for COVID-19. If I want to keep working at my job as a professor, I have to take this vaccine. Here’s my conundrum. My school employs me to be an authority on the subject of ethics. I hold a PhD in ethics and ancient philosophy, and I am here to tell you it’s ethically wrong to coerce someone to take a vaccine. If it happens to you, you don’t have to do it. If you don’t want a COVID vaccine, don’t take one. End of discussion. It’s your own business.

But that is not the approach of the University of Western Ontario, which has suddenly required that I be vaccinated immediately or not report for work. So with the school year beginning in a few days, I am facing imminent dismissal after 20 years on the job because I will not submit to having an experimental vaccine injected into my body. I have had plenty of vaccines in my life, but I have never been forced to take one. It’s always been my choice. I don’t work in a high-risk environment; I am not a doctor in an emergency room. I am a teacher. I am a university professor. My job is to teach students how to think critically, to ask questions that might expose a false argument. Questions like “Says who? Who’s the authority giving this order? Should I trust them with control over my body?” As a professor I don’t have to watch the news to find out if the COVID vaccines are safe. I read medical journals and I consult my colleagues who are professors of science and medicine. I have learned from doctors that there are serious questions about how safe these vaccines really are. There are questions about how well they work. Nobody is promising that I won’t get COVID or transmit COVID if I get the vaccine.

But ultimately none of that matters to me because I am a professor of ethics and I am a Canadian. I am entitled to make choices of what does and does not enter my body regardless of my reasons. If I am allowed back into my university, it’s my job to teach my students that this is wrong. I am hired to teach them that it is ethically wrong to impose an experimental medical procedure as a condition of employment.

This is my first, and potentially my last, lesson of the year. Ethics 101. In the spirit of Socrates, who was executed for asking questions, this lesson will consist of only one question. The answer is multiple choice. Please listen carefully. When a person has done the same job, to the satisfaction of her employer for 20 years, is it right or is it wrong, to suddenly demand that they submit to an unnecessary medical procedure in order to keep their job. In this case the procedure is an injection of a substance that has not been fully tested for safety. It has not yet been shown to be effective. It is designed to prevent an illness that poses little threat to the employee. The employee is not allowed to ask questions. She may only submit to the procedure or be fired. To my first-year students: is this right or is this wrong? I already know the answer.”

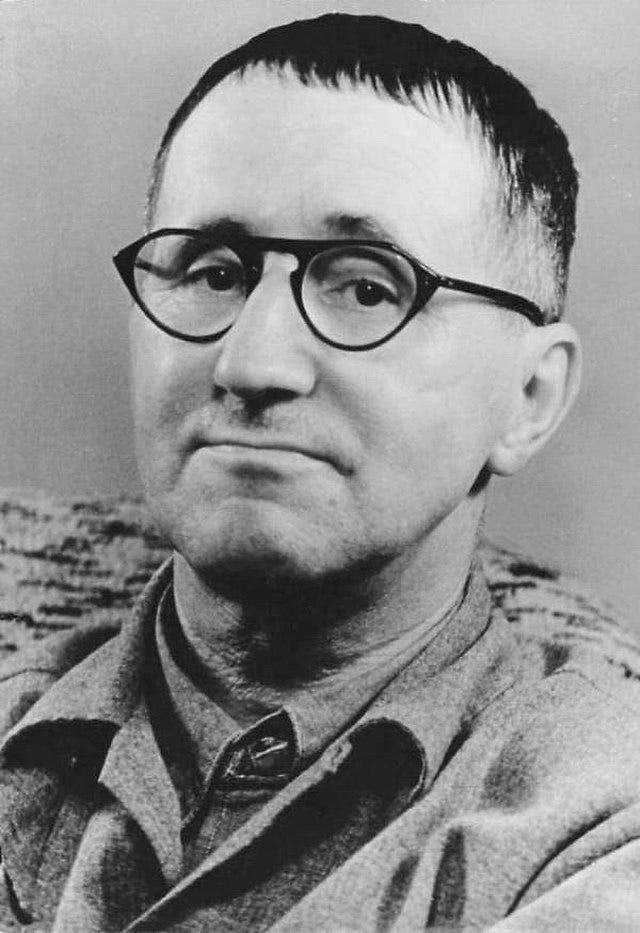

From Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo

When the exiled German playwright Bertolt Brecht wrote The Life of Galileo in 1938, he no doubt had in mind not only the early-modern struggle to convince people that the earth was not at the centre of the universe, but also the suppression of free thinking and expression under the totalitarian regime from whence he had fled.

In the beginning of the play, Brecht depicts a Galileo who naively believes that evidence and scientific truth are culturally “seductive:” if people are given the opportunity to examine telescopic evidence that the sun is at the centre of the solar system, they will embrace the truth enthusiastically. At that point, Galileo believes that his genuine passion for truth-seeking empirical inquiry is entirely compatible with his socio-economic interests.

However, Galileo soon realizes how wrong he is: in reality, most people will follow the narratives endorsed by local authority as if those narratives were truth itself. The idea that the earth was at the centre of the universe was important to the catholic church at the time because it apparently corresponded to Biblical descriptions of the sun moving in the sky, for example when Joshua asks God to perform a miracle so that the Israelites may win their battle against the Amorites still in daylight: “And the sun stood still, and the moon stayed, until the people had avenged themselves upon their enemies” (Joshua 10:13; https://biblehub.com/joshua/10-13.htm), or in Psalm 19, which describes the sun as a bridegroom who is joyfully on his way to claim his bride:

(1) The heavens declare the glory of God,

the dome of the sky speaks the work of his hands.

(2) Every day it utters speech,

every night it reveals knowledge.

(3) Without speech, without a word,

without their voices being heard,

(4) their line goes out through all the earth

and their words to the end of the world.

In them he places a tent for the sun,

(5) which comes out like a bridegroom from the bridal chamber,

with delight like an athlete to run his race.

(6) It rises at one side of the sky,

circles around to the other side,

and nothing escapes its heat.

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm%2019&version=CJB

Geocentric cosmology thus helped to assert an authoritative worldview that did not challenge established narratives in unsettling ways and that discouraged people from asking potentially heretical questions, for example about the plurality of worlds: if the earth is not at the centre, could it be that there are other plants hosting life? Why are those planets not described in the Bible? Would this mean that our humanity on this planet is not so central or precious to God?

The ideas, widely accepted among many believers today, that many of the descriptions of the heavenly bodies in the Bible are metaphorical, that the Bible is not a cosmology textbook and that God wants human beings to study the “book of Nature” empirically were rejected by Galileo’s enemies.

Many people in Galileo’s time believed that their wellbeing was ensured by the narratives endorsed by the church. The character of the Little Monk tells Galileo, “We must be silent from the highest of motives: the inward peace of less fortunate souls” who take comfort in thinking that their own special planet is stably positioned at the centre of the universe.

Galileo struggles with the dilemma of whether to embark on a principle-based peaceful opposition and speak out against cosmological truth. At times, Galileo seems to think that speaking out is a duty:

LITTLE MONK: You don’t think that the truth, if it is the truth, would make its way without us?

GALILEO: No! No! No! As much of the truth gets through as we push through.

Ultimately, however, the fear of torture or burning at the stake makes Galileo recant:

FEDERZONI: The question is whether you can afford to remain silent.

GALILEO: I cannot afford to be smoked on a wood fire like a ham.

Galileo honestly confirms that the need to make a living and to enjoy a certain lifestyle can be a powerful tool of coercion: “I cherish the consolations of the flesh. I have no patience with cowards who call them weaknesses. I say there is a certain achievement in enjoying things.”

Thus, on the surface, the play asserts that human beings are governed by socio-economic considerations—thus rejecting heroism and acting on principle:

ANDREA: Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero.

GALILEO: Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.

But even though Galileo refuses to be a martyr, his intellectual passion for the truth is impactful. Other people pick up the fight and smuggle his book out of Italy. The rest is in the history of science.

Cursory notes in response to the questions

(1) Under COVID, what does it mean to make decisions out of principle? What does it mean to make decisions pragmatically? Can you think of examples of decisions that you have made pragmatically and decisions that you have made out of principle?

Many people have endorsed the belief that, for those at low risk for severe disease due to COVID-19, getting vaccinated is a matter of principle: doing the right thing to help vulnerable people. That principle also corresponds to widely accepted official narratives, and so following it does not typically result in negative socio-economic consequences. This raises the question of whether people who follow that principle are really following a principle or are rather following the pragmatic socio-economic need to make a living and/or to feel a sense of belonging.

Other people believe in the principle that getting vaccinated should be an individual choice and that people who choose to not get vaccinated should not be punished, especially in light of empirical evidence that vaccinated people get and transmit COVID and that natural immunity provides better protection against future variants than the vaccine.

People who do not believe that the vaccine is necessary for them for medical or ethical reasons but still get vaccinated are typically doing so for pragmatic reasons: out of fear of negative consequences, such as job or social loss, and/or due to the desire to feel a sense of belonging or to avoid conflict. Some people who get vaccinated for pragmatic reasons are choosing at the same time to speak out about their view that vaccination should be an individual choice. In that sense, they are upholding the principle of free choice and free speech while making a pragmatic decision to get vaccinated.

Two thought-provoking resources that are critical of COVID culture are the following essay (and related essays on Julius Ruechel’s blog): <https://www.juliusruechel.com/2021/07/the-emperor-has-no-clothes-finding.html>, as well as the podcast Trish Wood is Critical <https://www.trishwoodpodcast.com>. Julius Ruechel describes the old wild horse who refuses to be tamed as a symbol for acting on principle.

(2) Compare and contrast Galileo (as depicted in Brecht’s play) and Julie Ponesse.

Today, Galileo is regarded as a hero who worked for scientific truth. In his own lifetime, however, Galileo was demonized for his evidence-based view that the sun was at the centre of the solar system and was threatened with torture and death if he did not recant (which he did, out of fear and pragmatism).

Your view of Julie Ponesse will likely be affected by whether or not you agree with her and accept her authority on ethics within the current cultural landscape. Reading ethics classics independently and then listening to her argument again can be enriching and helpful.

Dr. Ponesse is making the point of acting out of principle. Galileo, in contrast, decided to not act out of principle. Perhaps this is partly because the consequences for Galileo would have been harsher and less reversible than a paid leave. Do you think that Galileo would have spoken out had he lived today, or would the socio-economic incentives been enough to keep him quiet?

(3) How has COVID changed or developed your view of ethics? Of science?

COVID culture provides a reminder that science and ethics should not be equated with policy. Science is a fluid and open process of empirical and rational inquiry. A policy should be presented honestly as the product of human decision making at a particular moment in time, and often with limited information and non-scientific factors and pressures involved. A policy is not the same as truth. We do know, given exhaustive empirical confirmation, that the earth is not at the centre of the solar system. We cannot say anything with this level of certainty about the vaccines. Therefore, statements such as, “you are not following the science,” often directed at people skeptical of COVID culture, really come down to a similar accusation to that directed at Galileo, “you are not following the official narrative.”

This is one of my concerns about a possible future dystopian society:

In general, I believe in acting pragmatically. However, there is one principle that I cannot compromise: the right to think freely and peacefully in a manner that might differ from widely accepted narratives. People who think freely naturally often also wish to express their thoughts and hopefully engage in conversation and meaningful communication. I am concerned about a futuristic dystopian society in which expressing thoughts that differ from official narratives will be automatically defined as a symptom of mental illness—evidence of delusional thinking that would disqualify a person from employment or other forms of social participation and belonging. Also, there are pharmaceutical substances that can interfere with a person’s ability to think clearly. And since we have “established” a precedent that the government essentially has the right to order the injection of substances into people’s bodies, we might, if we are not vigilant, end up living in a dystopia in which the very right to think freely—if one dares to express the content of one’s thoughts—is socially and pharmaceutically removed. This might lead some people, in this future dystopia, to not express their thoughts and live a life of playacting and lies in order to avoid poverty and/or being chemically controlled. And without meaningful free expression, will the ability to think freely die a quiet death as well?

Excellent article! I think we are standing very close to the abyss - our right to speak is rapidly slipping away and I agree with your concern about being "diagnosed" with mental illness for wrongthink. What happened to Dr. Francis Christian suggests they are already thinking along those lines. Thanks for a great piece!

Very nice article indeed! Just wanted to note that the link to 'Trish Wood is Critical' is the wrong link, just in case people stumble into this Substack and want to listen to that podcast.