I have a bit of a pet peeve about the expression that sometimes comes up in the context of gift giving, “what do you give a person who already has everything?” This cliché strikes me as a somewhat self-congratulatory and smug way in which to position the would-be receiver of the gift in relation to the human condition and to time-honored traditions of gift-giving. By figuring gifts as burdensome additions to preexisting abundance, do we imagine ourselves to be less vulnerable than we actually are, less dependent on the good will of other people than we actually are? Have we forgotten that the prosperity that has been given can be taken away?

Sometimes people suggest consumable gifts as the solution of what to give to the person who already has everything—perhaps local strawberries when they are in season.

In Shakespeare’s Richard III, as Richard is scheming to seize power, his attention suddenly shifts to strawberries. Richard tells the Bishop of Ely:

“My lord of Ely, when I was last in Holborn

I saw good strawberries in your garden there;

I do beseech you, send for some of them.” (3.4.32-4)

Shakespeare draws here upon an incident that Thomas More records in his 1513 History of King Richard The Third, showing how quickly Richard shifts from lightheartedness to rageful paranoia:

“Whereupon soon after, that is to wit, on the Friday, the thirteenth day of June [1483], many lords assembled in the Tower. . . These lords so sitting together speaking of this matter, the Protector [Richard] came in among them, first about nine of the clock, saluting them courteously, and excusing himself that he had been from them so long, saying merrily that he had been asleep that day. And after a little talking with them, he said unto the Bishop of Ely: ‘My Lord, you have very good strawberries at your garden in Holborn, I require you, let us have a mess of them.” ‘Gladly, my Lord,’ said he. ‘Would God I had some better thing as ready to your pleasure as that.’ And therewith in all the haste he sent his servant for a mess of strawberries. The Protector set the lords fast in talking, and thereupon praying them to spare him for a little while, departed thence. And soon after one hour, between ten and eleven, he returned into the chamber among them, all changed with a wonderful sour, angry countenance, knitting the brows, frowning and frothing and gnawing on his lips, and so sat him down in his place, all the lords much dismayed and sore marveling of this manner of sudden change, and what thing should him ail. Then when he had sat still awhile, thus he began: ‘What were they worthy to have that plan and imagine the destruction of me, being so near of blood unto the King, and Protector of his royal person and his realm?’ At this question, all the lords sat astonished, musing much by whom this question should be meant, of which every man knew himself clear. Then the Lord Chamberlain, as he that for the love between them thought he might be boldest with him, answered and said that they were worthy to be punished as heinous traitors, whosoever they were. And all the others affirmed the same.”

The “sudden change” of Richard from a “merry” person who sleeps in and wakes up with a passion for strawberries into a tyrant who strikes fear into those around him makes us wonder whether Richard genuinely desires strawberries or whether strawberries only mask the true craving that gnaws at him—power.

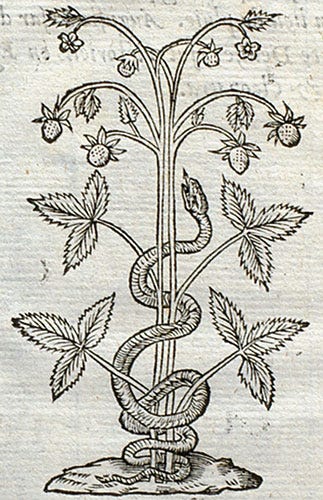

In “The Meaning of Strawberries in Shakespeare,” Lawrence J. Ross mentions, among other contexts, the association of strawberries with the line from Vergil’s Eclogues “latent anguis in herba” (there is a snake in the ground). The picture reproduced in this blog from the following website shows how the idea that a snake can bite one while one picks strawberries was also linked to the danger of being influenced by destructive ideas:

https://www.emblems.arts.gla.ac.uk/french/emblem.php?id=FPAb040

In a recent interview, Mark Carney was asked, in French, whether he buys strawberries from the United States. Carney responded that he must give a strange answer because as Prime Minister, he no longer buys strawberries and things of that sort; someone else does that for him (this is a rough translation of Carney’s French response).

https://x.com/eliasmakos/status/1908016801180446942

Carney’s answer seems to stand in contrast to Richard, who takes keen interest in what is in season and available for his enjoyment. While Richard possibly uses his enthusiasm for the local harvest of strawberries to conceal his desire for power, Carney candidly admits that shopping for produce is below someone with so much power as the Prime Minister.

To be fair, the question about strawberries directed at Carney was somewhat empty. One does not expect to run into the Prime Minister—be they liberal or conservative—in a grocery store. However, the skill of a Prime Minister should be to respond to any question by commenting on an issue that is relevant to Canadians, for example, to shop or not to shop for US produce. Instead, Carney responded in a manner that reminded us of his status and special position. He has transcended, it seems, the world of ordinary tasks and preoccupations and has ascended to the realm of grand responsibilities.

In William Shakespeare's As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Cliff Cardinal addresses the audience directly to challenge the assumption that hard work and intelligence are the primary explanations of socioeconomic success:

“You know how I know you didn’t get all this because of hard work: strawberry pickers work a lot harder than you. Beat [of a drum]. Must be because you’re so smart? Beat. Smart enough not to be a strawberry picker?” (p. 23).

One could add that some people are not only smart enough to not be strawberry pickers—they are also smart enough to navigate themselves to positions where they do not have to bother about grocery shopping at all. And from that elevated position, they send the message that we should be grateful that they have agreed to take care of us.

Carney seems so natural as he asserts his position as a hard-working Prime Minister that it might come across as unreasonable to question the depth of his loyalty and commitment. But is it relevant that Carney’s term as Governor of the Bank of Canada was the shortest in the Bank’s history because in 2013, he decided to leave to become the Governor of the Bank of England?

https://www.bankofcanada.ca/about/governing-council/historical-leadership-bank-canada/

Carney is often praised for his impressive CV, but if CVs are defined as impressive partly by the number of items on them, does this not create an incentive to leave positions, as well as bias against more loyal people who do not leave positions before their term is over because they have looked for “better” opportunities for themselves?

Because Canadians do not vote for the Governor of the Bank of Canada and because the position is not highly visible on a daily basis, Canadians generally do not tend to have strong feelings about whether the position is done by one individual or another. We tend to perceive the position as essentially technocratic. For that reason, Carney’s departure in 2013 was likely not experienced by many members of the public as Carney “dumping” Canada, even though he might have been (as far as I can infer from the list of Governors and the years of their service on the Bank’s website above) the only Governor who did not complete his term because he made a decision to take another position. The only other Governor to not finish his term, as far as I can tell, was James Coyne in 1961, and that was due to what came to be known as a the “Coyne affair” rather than due to a decision to take another position:

This tendency to not pay much attention to the fact that Carney decided to leave one of the highest positions of responsibility in Canada before his term was finished makes it possible for him to present himself now as a loyal Canadian who returned from a glowing international career to serve his homeland. Carney’s return to Canada reminds me of the (colonial) trope the dashing naval officer who returns from adventures at sea to claim higher status in his home country.

But as Shakespeare shows us, not every ambitious adventure is a success story. Shakespeare staged his tragedies in a theatrical environment in which the audience expected melodramatic events such as murder. But beyond these conventions, Shakespeare provides us with insights about character that apply to milder, non-criminal situations. So when Macbeth is telling Lady Macbeth that he will not go ahead with the plan to murder King Duncan so that he, Macbeth, would become king (but soon changes his mind under pressure from Lady Macbeth), his words remind us that also in less extreme situations that do not involve murder, casting aside a position of responsibility that one was privileged to receive might not be a constructive plan:

We will proceed no further in this business.

He hath honored me of late, and I have bought

Golden opinions from all sorts of people,

Which would be worn now in their newest gloss,

Not cast aside so soon. (1.7.34-38)

When contemplating Carney not simply as a duty-bound hero who has returned home to serve but as a person who in the past “cast aside” Canada, another trope that comes to mind is that of the “resurrected dumper”—a person who comes back to claim what years earlier they discarded. Even though this trope tends to be most intense in romantic contexts, the underlying principles apply to other spheres of action as well. The Netflix series Sex/Life depicts the fantasy that a woman can reconnect with an old lover while also enjoying the “benefits” of a stable and loving husband—whom through her own betrayal she manages to shape into an ex-husband who metamorphoses into a “cute and responsible co-parent.”

The novel Pain by the Israeli writer Zeruya Shalev presents a more sobering treatment of the “resurrected dumper” trope. Iris, the victim of a terror attack, is suffering from chronic pain. The doctor at the pain clinic that she goes to turns out to be no other than Eitan, an ex-boyfriend who decades earlier had dumped her. Now twice divorced, Eitan is inspired by the chance meeting to want Iris back. But for Iris, who is in a stable, albeit stale, marriage, the stakes are higher, and there is much to lose by becoming obsessed with the idea that Eitan is in fact her true “resurrected” love. Ultimately, Iris realizes that the affair with Eitan puts her “in her own land of Egypt” (127)—an allusion to the slavery that the Israelites were liberated from on Passover.

In this way, Pain shows how the “resurrected dumper” might in reality be an enslaver who threatens stability and prosperity. These lessons about liberty could also apply in the public domain. Specifically, how will Carney’s return to Canada affect the liberty of the Canadian people?

Had Canada not had a snap election, the election would have taken place in autumn, a time often associated in literature with fullness and sober self-reflection. Instead, the election will take place shortly after Easter (celebrating the resurrection of Carney as a Canadian savior?) and Passover (a holiday focusing on freedom). But Carney’s first day as Prime Minister on March 14, 2025, happened to be the Jewish holiday of Purim, commemorating the story of Esther.

Tamara Lich, one of the organizers of the truckers Freedom Convoy opposing COVID measures, wrote this about her time in jail in Ottawa:

“I spent a lot of time reading the story of Esther. When I left Medicine Hat [, Alberta], people kept telling me I was their Esther, but I didn’t really remember the story about her. It’s a beautiful story about how she stood up bravely to her husband, the king, and saved her fellow Jews. Even wives weren’t supposed to stand up to the king and she could have been killed for it. She risked her life to save her people” (176).

How will these people in Medicine Hat who saw Lich as their Esther fare under Carney?

On March 11, 2025, Nili Kaplan-Myrth, the Ottawa doctor who gained notoriety during the COVID period for her outspoken attitudes in favor of COVID measures, wrote the following column in the Ottawa Citizen: “Ella-Grace Trudeau, Cleo Carney—and my daughter—represent a new generation of hope.”

https://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/ella-grace-trudeau-cleo-carney-and-generation-of-hope

The focus of Kaplan-Myrth’s column is to describe Carney and Trudeau’s daughters, as well as her own daughter, as embodiments of hope and resilience for Canada’s future. Indifference to the suffering of Jews is one of the challenges that Kaplan-Myrth mentions her daughter has had to contend with: “She felt confusion and disappointment after October 7, 2023, when NDP politicians she knew personally did not show up to stand beside her at memorials for the Jewish community, let alone to Holocaust remembrance events.” And in the same brief column, Kaplan-Myrth also writes about her daughter who was in attendance at the Liberal leadership convention that “[s]he soaked up the electric energy of the room, and cheered when Carney was announced as the next party leader.” The juxtaposition of the two observations creates the implication that we should not be concerned when it comes to Carney’s response to antisemitism. This is not a sentiment that everyone would feel with confidence, given that attitudes toward Israel have been the key arena through which antisemitism has been spreading (antisemitism operates like a virus that in every stage of history metamorphoses into the form that would enable it to take root):

https://nationalpost.com/opinion/mark-carney-follows-trudeaus-anti-israel-lead

An April 12, 2025, Toronto Star article reports that “Carney promised that his government would make it a criminal offence to intentionally obstruct access to any place of worship or to threaten people attending services.” Carney is quoted as saying that “if any Canadian can be threatened when simply exercising a fundamental freedom. . . all of our freedoms as Canadians are at risk.” One wonders how this statement is consistent with the fact that on February 7, 2022, Carney called the Freedom Convoy “sedition.” Carney is correct about the fact that places of worship should be protected (it should be noted that the right to attend these places was not protected during the COVID period)—but in itself, the promise to protect synagogues is a rather self-evident response to antisemitism that any Prime Minister would have to make.

Another gesture toward the Jewish people that Carney performed this Passover was to prepare and eat matzo ball soup:

I love matzah ball (kneidlach) soup, gefilte fish and other Ashkenazi Passover dishes because they evoke childhood memories from my grandparents’ home. Eastern-European Jewish food is not, however, a universally loved cuisine. About half of Israeli Jews are not Ashkenazi, and many of them did not have parents or grandparents who made kneidlach. I was reminded of that fact on Israeli TV this past Passover when one panelist on a talk show made a sarcastic reference to “the kneidlach eaters” to make fun of Ashkenazi Israelis. In the novel The Lover, the Israeli writer A.B. Yehoshua reminds us, through the character of Na’im, an Arab who is invited to dinner at a Jewish home, what Ashkenazi food (in this case gefilte fish) can taste like to those who did not develop an emotional attachment to it in their childhood:

“To start with it was sort of gray meatballs, so sweet they made me feel sick. Looks like this woman doesn’t know how to cook, she puts in sugar instead of salt, but nobody else noticed or maybe they thought it wasn’t polite to mention it. And I forced myself to eat it too so she wouldn’t be offended like my mother, who’s offended if you don’t eat everything. I just ate a lot of bread with it to try and kill the sweetness. And that Adam ate so fast, I hadn’t had time to look at the food and he’d already finished it all. They brought him some more and he gobbled that up too. And I was eating slowly because I had to be careful to eat with my mouth closed and luckily the girl was eating slowly too so the grownups didn’t have to wait only for me. At last I finished those disgusting meatballs. I’ve never eaten anything like them before and I hope I never will again. I asked them what they were called so I could avoid them if ever I fell into a Jewish house again. They smiled and said, “It’s called gefilte fish. Would you like some more?” I said, “No thank you,” in a hurry. And the woman said, “Don’t be shy, there’s plenty more,” but again I said quickly, “No thank you, I’ve had enough,” but she’d already gotten up and gone to the kitchen and fetched a full plate and again I said, as firmly as I could without offending her, “No, really, I’m full, no more, please.” (168-169)

So yes, Carney has the courage to eat kneidlach. Gefiltefish in jelled broth would be the next step. But does he have the courage to confront the current metamorphosis of antisemitism? In the context of a terrible war that the Hamas passionately started on October 7, 2023, does he have the humility to not assert false superiority over the many people in Israel who are much more knowledgeable than he is about the situation and who have genuinely pursued peace but failed when the leaders on the other side were unwilling to abandon the fantasy that Israel is a temporary reality? Will Carney be putting a word salad and a rotten deal on the table for Jewish Canadians and for all Canadians? Want to belong? Want to be counted in as a “good liberal Canadians? Then will you have to accept a world in which Carney is “fighting antisemitism” while also equivocating and pandering to Israel hate? Unfortunately, this “deal” would be a delusion because a person who is genuinely interested in resisting antisemitism must acknowledge that antisemitism has metamorphosed into an obsession with the vilification of Israel, home to about one half of the Jewish people, while minimizing or ignoring the desire of its enemies to destroy it. In today’s world, one can enjoy the tropes of antisemitism as long as one is careful to say “Zionist” instead of “Juden”—and the Palestinians suffer partly because Israel haters worldwide have been implicitly emboldening the most destructive leaders among the Palestinian’s instead of demanding acceptance of the existence of Israel, without which any peace agreement is bound to fail, and without which the majority of Palestinians who want to live peacefully will continue to be ill served by their leaders.

Protecting Canadian Jews from antisemitism while pandering to Israel hate under the claim of caring for human rights is like trying to treat AIDS without acknowledging that HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, exists. Concern for human rights is important—and human rights will be best protected when Palestinian leaders abandon the active desire to destroy Israel, which has brought a great deal of suffering upon the Palestinians. The antisemitic tropes that are being revived today developed during the two millennia in which the Jews had no state of their own and were dependent on the good will of their non-Jewish neighbors and leaders. Ironically, it is the very existence of a Jewish state that now enables these tropes to flourish outside of Israel because it is no longer polite to be openly antisemitic, but it is polite to vilify Israel while claiming to be motivated by concern for human rights. Leaders who promise that they will “protect” Jews while at the same time exhibiting ignorance, hypocrisy and equivocation when it comes to Israel’s tragic obligation to defend itself are implicitly recreating a world in which the Jews are at the mercy of the whim of whoever happens to be in charge. And they are not helping the Palestinians, who are indeed suffering, and who need a leadership that will abandon the delusion of destroying Israel and will seek genuine co-existence that will benefit the majority of people who want to live peacefully.

In his memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness, Israeli novelist Amos Oz remembers November 30, 1947—when the UN decided on a partition plan for the British mandate of Palestine (this was one of several missed opportunities over the decades for the Palestinians to have their own state). Oz was eight years old at the time, growing up in Jerusalem:

". . . strangers hugged each other in the streets and kissed each other with tears, and startled English policemen were also dragged into the circles of dancers and softened up with cans of beer and sweet liqueurs, and frenzied revelers climbed up on British armored cars and waved the flag of the state that had not been established yet, but tonight, over there in Lake Success, it had been decided that it had the right to be established. And it would be established 167 days and nights later, on Friday, May 14, 1948, but one in every hundred men, women, old folk, children, and babies in those crowds of Jews who were dancing, reveling, drinking, and weeping for joy, fully one percent of the excited people who spilled out onto the streets that night, would die in the war that the Arabs started within seven hours of the General Assembly’s decision at Lake Success—to be helped, when the British left, by the regular armed forces of the Arab League, columns of infantry, armor, artillery, fighter planes, and bombers, from the south, the east, and the north, the regular armies of five Arab states invading with the intention of putting an end to the new state within one or two days of its proclamation. But my father said to me as we wandered there, on the night of November 29, 1947, me riding on his shoulders, among the rings of dancers and merrymakers, not as though he was asking me but as though he knew and was hammering in what he knew with nails: Just you look, my boy, take a very good look, son, take it all in, because you won’t forget this night to your dying day and you’ll tell your children, your grandchildren, and your great-grandchildren about this night when we’re long gone. And very late, at a time when this child had never been allowed not to be fast asleep in bed, maybe at three or four o’clock, I crawled under my blanket in the dark fully dressed. And after a while Father’s hand lifted my blanket in the dark, not to be angry with me because I’d got into bed with my clothes on but to get in and lie down next to me, and he was in his clothes too, which were drenched in sweat from the crush of the crowds, just like mine (and we had an iron rule: you must never, for any reason, get between the sheets in your outdoor clothes). My father lay beside me for a few minutes and said nothing, although normally he detested silence and hurried to banish it. But this time he did not touch the silence that was there between us but shared it, with just his hand lightly stroking my head. As though in this darkness my father had turned into my mother. Then he told me in a whisper, without once calling me Your Highness or Your Honor [the nicknames he usually used for his child], what some hooligans did to him and his brother David in Odessa and what some Gentile boys did to him at his Polish school in Vilna, and the girls joined in too, and the next day, when his father, Grandpa Alexander, came to the school to register a complaint, the bullies refused to return the torn trousers but attacked his father, Grandpa, in front of his eyes, forced him down onto the paving stones in the middle of the playground and removed his trousers too, and the girls laughed and made dirty jokes, saying that the Jews were all so-and-sos, while the teachers watched and said nothing, or maybe they were laughing too. And still in a voice of darkness with his hand still losing its way in my hair (because he was not used to stroking me), my father told me under my blanket in the early hours of November 30, 1947, 'Bullies may well bother you in the street or at school someday. They may do it precisely because you are a bit like me. But from now on, from the moment we have our own state, you will never be bullied just because you are a Jew and because Jews are so-and-sos. Not that. Never again. From tonight that’s finished here. Forever.' I reached out sleepily to touch his face, just below his high forehead, and all of a sudden instead of his glasses my fingers met tears. Never in my life, before or after that night, not even when my mother died, did I see my father cry. And in fact I didn’t see him cry that night either: it was too dark. Only my left hand saw." (477-80)

Any leader who wishes to protect Jews from antisemitism must deeply understanding this sentiment that Oz’s father expressed. It was a sentiment that was widely shared among persons in my grandparents’ generation and that stood at the heart of Zionism and of their decision to immigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine: the feeling that the existence of Israel is necessary to protect Jews from antisemitism because figures of authority in other countries cannot be consistently trusted to protect their Jewish citizens and treat them as equal. The determination to “never again” be at the mercy of those who enjoy the pleasures of Jew hate might seem hysterical to people who grew up in the post-World-War-2 West, but it was strongly rooted in the lived experience of many Jewish persons of my grandparents’ generation and earlier generations—culminating in the Holocaust. Anti-Israel activists sometimes express patronizing “empathy” for Jewish inter-generational trauma as they gaslight us to believe that we are only “imagining” the rise of antisemitism due to that trauma. It seems to me that one of the talking points that polite Israel haters might be taught by their influencers is to acknowledge our inter-generational trauma before asserting moral superiority over us. They are wrong that we are only imagining. The demonization of Israel and the desire to destroy it are real, and in a society in which Israel hate runs wild, Jews are not free and equal citizens; they can only try to be so if they hide their Judaism (good luck!) or if they subjugate themselves to Israel haters and take on the unfree role of “the Jew who agrees with me.” Leaders who pander to Israel hate are making a mockery of their obligation to protect their Jewish citizens and all their citizens and are reminding us of the reasons that Zionism came to be in the first place—the feeling that when leaders have to choose between protecting Jews or pandering to their haters, they will too often choose the latter—and sometimes do so with glee. In the extreme context of the Holocaust, we know how this ended. Consider, for example, the following account from Christopher R. Browning’s Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland:

“After entering the city of Białystok [in Russia], Major Weis on June 27 [1941] ordered his battalion to comb the Jewish quarter and seize male Jews, but he did not specify what was to be done with them. That was apparently left to the initiative of the company captains, who had been oriented to his way of thinking in the preinvasion meeting. The action began as a pogrom: beating, humiliation, beard burning, and shooting at will as the policemen drove Jews to the marketplace or synagogue. When several Jewish leaders appeared at the headquarters of the 221st Security Division of General Pflugbeil and knelt at his feet, begging for army protection, one member of Police Battalion 309 unzipped his fly and urinated on them while the general turned his back” (11-12).

For a person who should be acutely aware of the trope of the leader who turns their back on the Jews, who should be acutely aware of how much some people dislike it when Jews are not subjugated but are in control of their own destiny, Kaplan-Myrth seems remarkably confident in our savior Carney:

https://www.threads.net/@nilikm/post/DICnrkRRADZ

I fear that Carney’s attitude of equivocation toward Israel will not help the Palestinian people but might make things worse for Jews in Canada, so Kaplan-Myrth’s enthusiasm for him seems somewhat naïve for a person who comes across as principled and uncompromising about the issues she cares about. Could it be that ambition might be clouding her judgement? In the title of Kaplan Myrth’s column, the dashes stand out: “Ella-Grace Trudeau, Cleo Carney — and my daughter — represent a new generation of hope.” Dashes are a paradoxical punctuation mark because they at the same time bracket off and emphasize what is enclosed within them. In this case, do the dashes ambivalently stand for ambition combined with social anxiety: a desire to assert that her daughter is a member of the club while not being quite sure about her status? Are those inside the dashes in the same club as those outside? Kaplan-Myrth implies that her daughter shares in the experience of the young generation of Canada’s elite:

“She has also witnessed firsthand the vitriol and harassment that is directed at those who step onto a public stage and understands the risk that people take by being politically active. She is intimately acquainted with the misogyny, antisemitism, anti-trans hate that was directed at our family as a result of stepping up for Ottawa, for the Jewish community, and for transgender rights. She has an inkling what Ella-Grace has been through, and what lies ahead for Cleo.”

But if the dashes might stand as visual symbols of the gates of the club, Kaplan Myrth might find that these gates do not yield easily to those ringing the bell. This is something that used to be evident in the experience of many Jews of my grandparents generation and before, but today we live in times of hypocrisy when antisemitism pretends to focus on Israel, so hope may spring eternal for Canadians who wish to believe that a person who equivocates and panders to Israel hate will not only protect them from antisemitism but will also accept them into the elite club as equal members.

And for those of us who are too thick to pass through the eye of the needle into the club, the question is, how much of our liberty will the people who “made it in” be willing to sacrifice in order to perform the required social cues?

The phrase “—and my daughter—” and Kaplan-Myrth’s confidence in Carney stand in my mind as a reminder of how principles (for example, the understanding that the current metamorphosis of antisemitism focuses on Israel and that Carney needs to answer hard questions about his equivocation) might be compromised when one can imagine oneself or one’s children enjoying the power and privilege that come with an actual or hoped-for elite “club” membership, when one wants to feel the sense of belonging that seems to be reflected in the following picture that Kaplan-Myrth shared of her daughter with Cleo Carney and another person:

And while games are unfolding on Mount Olympus, can the rest of us hope to enjoy a reasonably prosperous life without compromising the love of liberty?

In “My Little Cabane,” the Irish born Canadian poet Henry Drummond (1851-1897) imagines a French-Canadian woodsman who, speaking English with a French-Canadian accent, is delighted with the few but cherished material possessions he has. Sitting in his cozy cabin with his dog’s head resting on his knee and with a fire blazing in a wood stove to keep him warm, the woodsman feels snug and safe from the howling wind of the winter storm. Here are the first three stanzas of this dialect poem, spoken in English with a heavy Quebecois French accent:

I'm sittin' to-night on maleetle ca-

bane, more happier dan de king,

An' ev'ry corner 's singin' out wit'

musique de ole stove sing

I hear de cry of de winter win', for de storm-

gate 's open wide

But I don't care not'ing for win'or storm, so

long I was safe inside.

Viens 'ci, mon chien, put your head on dere,

let your nose res' on ma knee-

You 'member de tam we chase de moose back

on de Lac Souris

An' de snow come down an' we los' ourse'f

till mornin' is bring de light,

You t'ink we got place to sleep, mon chien,

lak de place we got here to-night

Onder de roof of de leetle cabane, w'ere fire

she's blazin' high

An' bed I mak' of de spruce tree branch, is lie

on de floor close by,

O! I lak de smell of dat nice fresh bed, an' I

dream of de summer tam

An' de spot w'ere de beeg trout jomp so

moche down by de lumber dam.

https://allpoetry.com/My-Little-Cabane

The woodsman’s feeling that in his modest home, snug against the storm raging outside, he is happier than the king (an English king ruling over French Canadians) turns this humorous poem into a serious statement about liberty: rather than feeling that the king knows best, the woodsman asserts that he himself holds the key to his own joy, which he seems to feel is abundantly available in a simple, private life defined by hard work, self-sufficiency and the luxury of being left alone in one’s home, with nature close by.

Compared to that of the woodsman, our condition today seems both softer and harsher. It is softer because materially, we want and we have much more than the woodsman—and in that way we have sometimes forgotten the meaning of realities such as poverty or war. And yet, our lives are harsher in the sense that it is not clear that we can partake in the optimism that the poem exudes about the possibility to be independent and happier than those in charge who might be hungry for control.

Writing in December 20, 2024 in the National Post about the Canadian cabinet shuffle that took place at that time, Don Braid pointed out the failings of the elite but also commented on a “bright side:”

“Great hair, though. As a group, these ministers of all genders stood out for their elegant and expensive winter coats, superb grooming, Grade A coiffures and excellent dental work. I found the effect nauseating. The display of easy affluence is so offside with a general public struggling with inflation, rent, housing and life in general. Few people could fail to see elite politicians simply delighted by their sudden ascent to power.”

With such affluence out of reach for many Canadians, a person pitching their ability to deliver must be able to offer solutions to Canadians who are justifiably anxious about the difficulty of affording housing and living reasonably prosperous lives. But equally important is whether we can live with liberty inside the homes that we own or rent.

The woodsman’s aromatic delight at the fragrance of the spruce-sourced bed that he built for himself brought to my mind, by way of contrast, Lich’s description of her bed in jail:

“. . . they put me into a tiny little cell with a metal toilet, a metal sink and a cement slab for a bed. It had been snowing and wet all day. My boots were wet. My sweater was wet. I asked for a blanket. They said they didn’t have one. I was freezing. I was exhausted. The concrete was sucking what little warmth I had out of my body. So I just waited there. Danny [Bulford] had told us that it was very likely if we were arrested, we would sign an undertaking and be released within hours, as this was the normal procedure. I figured I would be out soon enough. That night, or the next day. The government was going to make sure I wasn’t” (Kindle location 2503-2509).

“I went back to solitary and I still didn’t have a book. I begged them even for a Bible. I was willing to take anything. But they wouldn’t give me anything” (Kindle location 2599). [she later got a Bible, as indicated above when Lich speaks about reading Esther.]

The fact that Lich did not get bail shortly after her arrest for “mischief” (for which she was convicted on April 3, 2025) was disproportionate, especially considering the general peacefulness of the Freedom Convoy. That was an outcome that de facto turned Lich into a political prisoner of a ruling class that demonized skepticism of COVID measures—this while later ignoring the hateful behavior that has unfolded in some anti-Israel demonstrations.

It is not my intention here to idealize people who were skeptical of COVID measures. As a person who is socially awkward and who is concerned about the normalization of Israel hate in our society, among other problems, I am not inclined to observe with naïve admiration any protest, any organized human activity, any leader, or any group of people—as all of us are flawed and vulnerable to blind spots. But at the same time, I did not perceive a grave threat to Canadian national security in the opposition to COVID measures, which should have been subject to more debate, and which at times seemed to coincide with what was convenient for the laptop class and with a cultural desire to normalize working from home. Working from home is often indeed a good idea (from which I personally benefit)—but it should have been discussed in its own right as a response to technological change rather than simply a response to a health emergency.

It is also difficult for me to view Lich through alarmist eyes when I read about how she writes about those who held opinions different than her own:

“Even though I had no confidence in the masking rules, you might be surprised to learn that I followed them when I had to. I wasn’t one of the people getting into fights with the clerks at the grocery store. I was never a jerk about it. If a store or a health clinic or something said they required me to wear a mask, then I put on a mask. I’d take it off the second I walked out the door. But I wasn’t about to ruin the day of some grocery clerk or nurse. These people were having a hard enough time working through all this as it was” (Kindle location 458-461).

“My oldest daughter is a nurse and she works for Alberta Health Services and she is very much in favour of masking and vaccination, and I respect her, and she respects me (we’re also both very respectful of avoiding getting into debates with each other). That’s freedom. And if there’s one thing I believe in, it’s that everyone should have the freedom to make their own choices” (Kindle location 469-472).

It is interesting to compare how Lich and Kaplan-Myrth each write about their respective daughters. In the column quoted above, Kaplan-Myrth writes that her daughter “shook with fury when the trucker convoy surrounded her middle school.” Kaplan-Myrth likely knows that these words would be antagonizing to the many Canadians who liked the Freedom Convoy. Is her daughter happy to be so publicly and definitively identified with a polarizing position? What if she changes her mind? Many people do not still hold positions that they did as teenagers. While Kaplan-Myrth’s daughter is depicted as possessing emotions of antagonism against the truckers that seem identical to those of her mother, Lich’s daughter comes across as her own person. The reference to the relationship between Lich and her daughter evokes memories of a world in which people could have sharp differences of opinions but still respect each other and remain friends.

It does not feel good to write sarcastically about a person who is not yet an adult. For this reason, I asked myself if it would be best to delete the references to Kaplan-Myrth’s daughter from this commentary. At the same time, there is a point about liberty that needs to be made in this context: if a parent makes a decision to publicly write about their teenage child in manner that implicitly demonizes people who do not agree with them and suggests that this child and their fellow “club members” embody our political future, then we do have the right to wonder whether the “innocence of youth” is being mobilized to control and manipulate us to not ask enough hard questions.

One of the achievements of Western individual liberty is to uphold the idea that the individual has the right to attempt to write their own story—to use their reason, emotion and innate identity to try to pursue what they think happiness means to them—as long as they do not break the law. This achievement is meaningful only if we can pursue our liberty while also enjoying reasonable prosperity and a sense of belonging and of being accepted and valued by others. Staying out of jail is not enough; most of us cannot “enjoy liberty” if the result is poverty and/or social exclusion. One of the failings of the communist, socialist and fascist movements of the twentieth century and of their possible resurrection today is that they purport to tell someone in an overly aggressive manner that authority figures know what is good for them. We should be wary of people who claim to know what is best, as it is often a way for them to exert power that erodes liberty.

One of the reasons that we may not perceive grave threats to liberty is that for quite a while now, the lives of many of us in the West have been significantly distant from war, poverty and want. However, contemplating Lich’s jailhouse bed side by side with the woodsman’s birch bed brings to mind a question that people who have transcended the need to grow, pick or shop for strawberries should be able to answer: in the world that you feel duty bound to provide, will it be possible for a person who loves liberty to be, in their own reasonably prosperous way, “more happier dan de” prime minister even if they disagree with the prime minister?

Even though I do not like the expression, “what do you give a person who already has everything?” when I think about the upcoming election, Carney strikes me as that man who has everything: he was granted the opportunity to be Governor of the Bank of Canada, and then on top of it he was given the opportunity before his term was finished to jump to the Governor position at the Bank of England, and then he made money in the private sector, and then he entered politics with the idea that we should be grateful for his willingness to serve. He already had a ball of kneidlach soup—and one serving of Ashkenazi food is likely enough for one season. Strawberries are not yet in season—and his staff would buy them for him anyway. I sense that he would want the one thing that I could give: some knowledge of Israel’s tragic predicament and of what it means to have enemy leaders who wish to wipe you and liberty off the face of the earth about as much as I would like to receive the gift of a root canal. There is likely only one thing Carney wants from me—my vote. So perhaps in this particular instance, the cliché that a person who has everything does not need more gifts might hold true.

References

Quotes from Shakespeare are from the Folger editions:

https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/

Browning, Christopher R. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

Cardinal, Cliff. William Shakespeare's As You Like It, A Radical Retelling. Playwrights Canada Press. Kindle Edition.

Lich, Tamara. Hold The Line: My story from the heart of the Freedom Convoy. Rebel News Network Ltd. Kindle Edition.

More, Thomas. History of King Richard The Third (1513)

https://thomasmorestudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Richard.pdf

Oz, Amos. A Tale Of Love And Darkness. HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

Ross, Lawrence J. “The Meaning of Strawberries in Shakespeare.” Studies in the Renaissance, Vol. 7 (1960), pp. 225-240.

Shalev, Zeruya. Pain: A Novel. Other Press. Kindle Edition.

Yehoshua, A. B. The Lover: A Novel (Harvest in Translation). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition

Source for image: https://www.emblems.arts.gla.ac.uk/french/emblem.php?id=FPAb040

You are subscribed to a doxxing spammer who uses ChatGPT to write all his posts.

He will demand you pay him or will dox you soon too. Be warned.